When folk singer Pete Seeger and some friends launched

the Clearwater sloop nearly 50 years ago, the Hudson River was a fish-killing open

sewer from industries and municipalities along most of its majestic sweep from

the Adirondack Mountains past Catskills views immortalized by the Hudson River

school of painters. Raw sewage sloshed with the tides lapping against former

swimming beaches below the towering Palisades cliffs in New Jersey, decimating

a declining shad fishing industry. It sloshed and bobbed amid the ocean liner piers

framed by Manhattan’s postcard scenic skyscrapers. The massive flow of

pollution continued into New York Bay, sloshing in wind-tossed waves rocking

Staten Island ferries, churning past the Statue of Liberty and out to sea, slimming

the striped bass fishing areas off Coney Island’s amusement park and ocean-view

beaches.

But then, the sight of a full-sail sloop tacking up

and down the tainted river with a crew of excited kids and adults picked up at

docks from Albany to Jersey City sparked outbursts of activism that produced

cleanups of major sources of pollution.

The inspiration for this hearty environmental activism was a beanpole-thin, blue-jeaned

guy who tramped around with a banjo singing old-fashioned folk songs. For

decades, Pete Seeger energized hand-clapping, standing-room-only audiences of

all ages in jam-packed high school auditoriums from White Plains to Montclair, in

throngs at the annual Clearwater Festival/Great Hudson River Revival in Croton

Point Park, and in a star-studded crowd at a 90th birthday bash cum Clearwater

fundraiser in Madison Square Garden. Seeger’s career as the pied piper of

environmental activism was capped by leading a television-watching nation in

singing “This Land Is Your Land” at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.

during the first inauguration celebration for President Obama.

“I’m more optimistic than I’ve ever been before,” Seeger said at an Earth Day

fair at Columbia University’s Teachers College in April 2009, where he was the

keynote speaker. His optimism was fueled by the computer-generated “information

revolution,” he said, which has sped up the process of exchanging good ideas.

“I now speak with people I never used to speak with—some on the left, some on

the right. I think, I believe, we will see more miraculous things happen,”

Seeger said. And then he launched into his trademark patter of story-telling

songs with an activism hook. Among these chestnuts was Seeger’s infectious

channeling of Martin Luther King Jr. and the hymn-based anthems of the civil

rights movement. The refrain of a favorite tune goes:

Don’t

say it can’t be done

The battle’s just begun

Another of Seeger’s infectious songs was inspired by a

zero waste campaign in Berkeley, California, which led to this memorable lyric:

If

it can't be reduced, reused, repaired

Rebuilt, refurbished, refinished, resold

Recycled or composted

Then it should be restricted, redesigned

Or removed from production

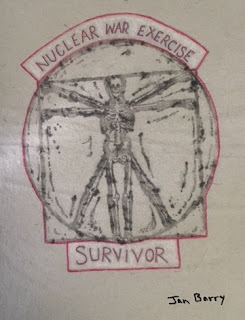

Cheerfully singing even as his health declined, Pete Seeger

died at 94 in January 2014. A World War II army veteran, he was an ardent peace

activist as well as environmentalist. In his view, the two issues were connected.

When the Clearwater campaign began, a major polluter was the U.S. Military

Academy at West Point, which flushed raw sewage into the Hudson River at its

picturesque, historic site in the Hudson Highlands. In his war protest songs,

Seeger prodded the Pentagon to clean up its contamination acts—bombing,

shelling, napalming and use of Agent Orange and other chemical warfare—in Vietnam.

Among other accomplishments, the innovative Clearwater campaign provided potent,

popular incentive for Congress and President Richard Nixon to pass the 1972

Clean Water Act, which forced West Point and Hudson River cities, including New

York City, to build upgraded sewage treatment facilities.

Singing and sailing up and down the Hudson, Pete Seeger encouraged people to enjoy

working to change things for the better. He invited diverse people—rural

people, city people, young people, older folks—to join him in an exciting

project: Build and launch a replica of a 19th-century river sloop. Take volunteer

crews and groups of school kids and community leaders out on the river and show

them the pollution and where it’s coming from. Raise funds to hire scientific

experts to testify at public hearings. Mobilize crowds of well-informed citizens

to attend and speak at public meetings. Organize festivals where musicians,

activists and audiences energize each other.

At Clearwater Festivals, concertgoers happily tramp through mud and rain to

hear a Woodstock-style weekend of musical acts—including Arlo Guthrie, Richie

Havens, Taj Mahal, the Hudson River

Ramblers—and to check out the wares at scores of tents set up by activist

organizations, handicraft makers and solar energy merchants. At a Clearwater

Festival a few years ago, a group of New York City high school students proudly

showed their newly learned skills in boat building and offered tours on the

river in hand-made wood reproductions of classic sailboat tenders. Nearby, a spritely,

eighty-ish Pete Seeger slipped into a rain-drenched tent with a banjo and

joined in a round of sea shanties with a motley crew of bearded old salts, one

of whom was wearing a battered Vietnam Veterans Against the War cap. With a tip

of his hat to the activist vet, Pete Seeger was off to his next networking gathering,

joining a stage full of folk song luminaries and belting out some more of his

favorite tunes.

Behind the scenes, the famous folk singer also oversaw a continuous array of outreach

expansions of evermore extensive Clearwater campaigns. These included, in

recent years, its Next Generation Legacy Project and the Clearwater Center for

Environmental Leadership, a youth education camping program in Beacon, NY, the

riverside town where Pete Seeger lived with his wife, Toshi, his partner in

organizing and in life since their marriage in 1943. Toshi Seeger died at

91 in 2013. Under their leadership, the Clearwater festivals, sloop sail rides

and other outreach activities challenged people in the Hudson Valley to find

solutions to seemingly intractable pollution.

The group’s stance in opposing a license renewal for

the Indian Point nuclear power plant--its cooling towers and radiation chambers

sucking in millions of gallons of Hudson River water and fish looming just

upriver from the music festival site—sparked an investigative project by

environmental students at Ramapo College of New Jersey, for instance. The

student report concluded that an energetic energy conservation program combined

with increased wind and solar power could replace the aging nuclear power plant

and negate its potential dangers of radioactive contamination of the river and

the region. Riding an increasingly popular environmental wave, New York

Governor Andrew Cuomo successfully pressed last year for the closing of Indian

Point’s two reactors by 2021. “The plant has grappled with 40 safety and

operational events and unit shutdowns in the past five years,” The New York Times dryly noted.

Despite all the activism stirred up by Clearwater

campaigns, there’s still a New York State advisory warning about eating fish

from the Hudson River. But a major source of contamination was greatly reduced

when General Electric dredged tons of PCBs from a heavily polluted stretch of

the river north of Albany, a reluctant clean up done due to a decades-long

battle by environmentalists. Manna Jo Greene, Clearwater’s environmental

director during much of that battle, noted the campaign to clean up hazardous

PCB pollution was “a classic grassroots effort, achieved in large part due to the

tireless and scientifically-based work of past and present Clearwater staff

members and volunteers, our collaborative partners in the Friends of the Clean

Hudson Coalition, and the hundreds of thousands of people who wrote letters,

signed petitions and cared enough to take action.”

Pete Seeger’s obituary in The New York Times channeled the spirit of this down to earth folk

singer: “Through the years, Mr. Seeger remained determinedly optimistic. ‘The

key to the future of the world,’ he said in 1994, ‘is finding the optimistic

stories and letting them be known.’ ”